Last week, I wrote about some of the key questions surrounding the U.S. withdrawal or rather violation of the JCPOA which focused on the responses of Iran (production, discounting, regional policy), Europe (blocking measures), and Asian buyers of Iranian goods. Since then the focus has been on the European counter response to the U.S. decision, and on assessing the energy market impact, and the potential risks to the use of sanctions as a policy tool. I provide a few follow up thoughts here.

Exit first, protection later: Many European companies seem to be preparing to freeze or reduce their investment, worried about the risks of future fines, despite pledges of blocking statutes. Developed markets in Asia are likely to be more cautious Meanwhile at the same time, European leaders are rushing to implement blocking legislation that would shield European companies from fines, and would forbid some companies (banks?) from implementing measures lest they face other fines. These measures have exposed divergent views between and within key European countries (notably France and Germany in recent days).

The blocking statute and other moves are in part one of principle in which the Europeans look to establish their concern about U.S. extraterritorial sanctions for the current and future cases, especially where U.S. and Europe have diverging views on the goals. Companies may choose to be cautious implementing cuts or freezing new deals given their concerns about the limited upside from trade in this environment, and fearing to loose access to U.S. markets. The net result is likely one of confusion, broader derisking as some companies scaling back activity won’t scale it back up without assurances from Iran. As others have noted, the imposition of sanctions may be the nail in the coffin for investments that were already on edge due to questions about the investment terms including some oil and natural gas contracts.

Oil: Oil volumes will be a major indicator for all to assess whether the process of undermining or stabilizing the deal is a success. The Trump administration is likely to look for reductions to show that sanctions are being implemented, while Iran would likely see volume drops as a sign of bad faith from trading partners, leaving European and Asian buyers in the middle. One key difference from 2012 is that EU member states quickly eliminated oil imports, leaving key Asian buyers and Turkey to take part in the “significant reductions” in imports. Europe is unlikely to do so this time given the political goals. Expect there to be greater uncertainty and debate around the metrics to use in tracking compliance. As noted, last week, OPEC+ may well act slower and less extensively than buyers hope, increasing price spikes and overall volatility.

The chart below highlights some of the countries that will be pressured to reduce imports. While it includes non-oil exports as well as fuel, it provides a useful breakdown. One thing that stands out is that Iranian exports to Europe and India experienced the greatest boost post-JCPOA, with volumes increasing more modestly to South Korea, Turkey and China, as these countries tried to balance their regional trade. Japan notably, barely increased trade from the pre-JCPOA levels (though the change in energy prices partly obscures the trend.

Iran exports have been increasing along with hydrocarbon prices (rolling 3 month sums, USD billion)

Source: IMF (via macrobond)

The OFAC guidelines suggest waivers would only be granted to those companies that show “significant” reductions in the coming months ahead of the November deadlines. Market analysts estimate export declines of 200-700 thousand barrels in the coming months, and more in 2019, quite a wide range in scope. complicating this, the definition of significant reductions is less than clear as the Trump administration hasn’t signaled whether they share the Obama administration definition of 10-20% declines over each six month period, or how they consider market price dynamics. Given the timing of decisions may continue to boost oil prices in the summer and fall as the mid-terms approach, these signals could be very important.

This suggests that companies looking to play it safe may reduce volumes, especially if the Iranians are unwilling to discount as Chinese and Indian buyers are likely asking for. Those countries that have already negotiated insurance or set up vehicles to do so in 2012-14 may be better positioned to maintain their market share or engage in barter agreements with Iran. Many Asian countries had to learn quickly to navigate the system to make sure their payments reached the Iranians in that period. European insurers or banks are likely to be much more worried than some of their EM Asian counterparts. This suggests that Chinese, Indian and Russian influence may increase.

Shares of Iranian Exports by Countries (% of total exports in USD terms)

Source: IMF (via Macrobond)

Impact on OPEC+ agreement: Many analysts see the sanctions decision as a risk to the OPEC+ (Vienna group) agreement which seeks to restrict output. Its definitely a test, and one likely to tighten the market further, particularly coming after massive declines from Venezuela and more moderate ones from Nigeria. The former’s almost 1mbd decline was partly absorbed by other countries cheating, but still resulted in quicker rebalancing of the market. In Iran’s case, other countries, most likely GCC countries like Saudi Arabia might respond by just directly selling more, rather than formally changing the deal. Recent statements from OPEC+ members don’t seem consistent with a group ready to start adding a lot more capacity – adding to uncertainty and the risk that new suppliers are slow and lower volumes than expected.

The ongoing trade threats and negotiations likely complicate oil decisions, amplifying the incentive for some actors to maintain their imports, and reducing it for others. Japanese and Korean companies, mostly government owned, may have high incentives to temper purchases to avoid fines, and perhaps to avoid retaliation in other ongoing trade negotiations and the planned DPRK discussions. Similarly, divergence in interests between European countries (Germany and France) may reflect ongoing negotiations on planned tariff implementation as well as the spillovers from Russia sanctions, not to mention different views on industrial policy (government support of companies) as well as the divergent sectors of interest in Iran. The net result is likely to be one in which China, already a dominant player in Iran (as a supplier, buyer and investor) increases its involvement. Meanwhile Russian interests could also increase, though its increased reliance on China and GCC as a source of long-term investment could muddy the waters there.

Impact on Iran’s economy: Many analysts believe that export declines might outpace that of production as Iran might seek to fill its relatively empty floating storage and might look to refine more products in the hopes of selling. While Iran might initially look to use a loophole and continue exporting products, such a loophole is unlikely to exist for long.

The overall impact on Iran’s economy is likely to be painful, especially coming in the midst of the ongoing currency crisis. A lag between production and export declines would shift the impact on Iran’s economy as oil sector contribution to GDP might slow more gradually (if at all) in the near term as output remains steady. However a reduction in sales would hit revenues and liquidity and likely constrain domestic demand via reduced government spending and lower domestic liquidity. FX shortages might reinforce these trends especially if the central bank continues its tight policy to temper inflation. Eventually, both exports and production might fall, hitting both oil and non-oil growth, as higher oil prices don’t offset for the volume losses. The concurrent reduction in (albeit limited) long-term investment would add to the drag, suggesting Iran’s growth could slow or even move towards recession.

Related imports (either for auto manufacture), energy projects or broader infrastructure are also likely to slow, especially if Iran struggles to make payments. This implies that Iran may become even more of a price taker on its imports, relying more on countries that buy its fuel. The full “escrow” account system that was much criticized in 2012-5 (it allowed for accrual of funds in local currency within oil consuming nations to purchase only approved goods), is unlikely to resume in the same degree, with financial transactions more leaky than at that point. Still, key consumers of fuel are likely to be direct or indirect suppliers, even as overall imports and the ability to pay for them declines.

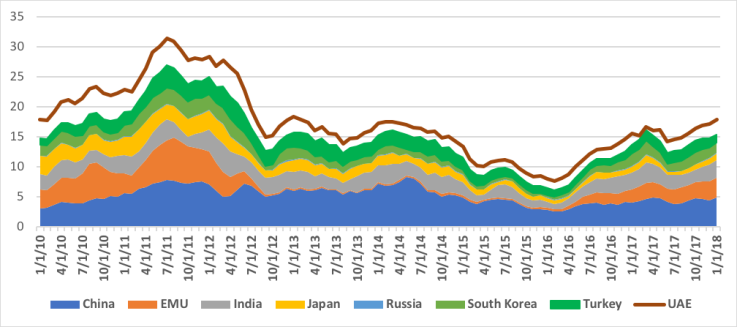

Imports have been trending up, especially from Europe and UAE (rolling 3 month sums, USD billion)

Source: IMF (via macrobond)